by Amy Speer | Fire Spotlight Contributor

Numerous light studies show fire truck light masts provide more usable light than portable or truck-mounted lights. Even the most basic fundamentals (which we’ll cover in a moment) back the advantages of elevated lighting. And yet, all too often, these masts are deemed an option. Rarely the standard. But still, an important choice that fire departments can make and advocate for when purchasing their apparatus, which brings us back to those fundamentals.

When it comes to nighttime vision, light uniformity (even lighting across the scene) is more important than intensity (extreme illumination of a particular area within a scene) because intensity can cause a breakdown of the eyes’ rhodopsin, a light-sensitive protein that activates the retina’s rod cells, which aid in nighttime vision. Moreover, this strain increases when a person’s eyes continually adjust from dim to bright lighting. This is where grouping lights on a light tower can be beneficial.

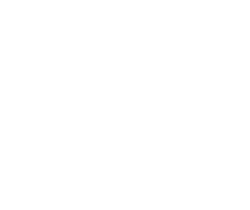

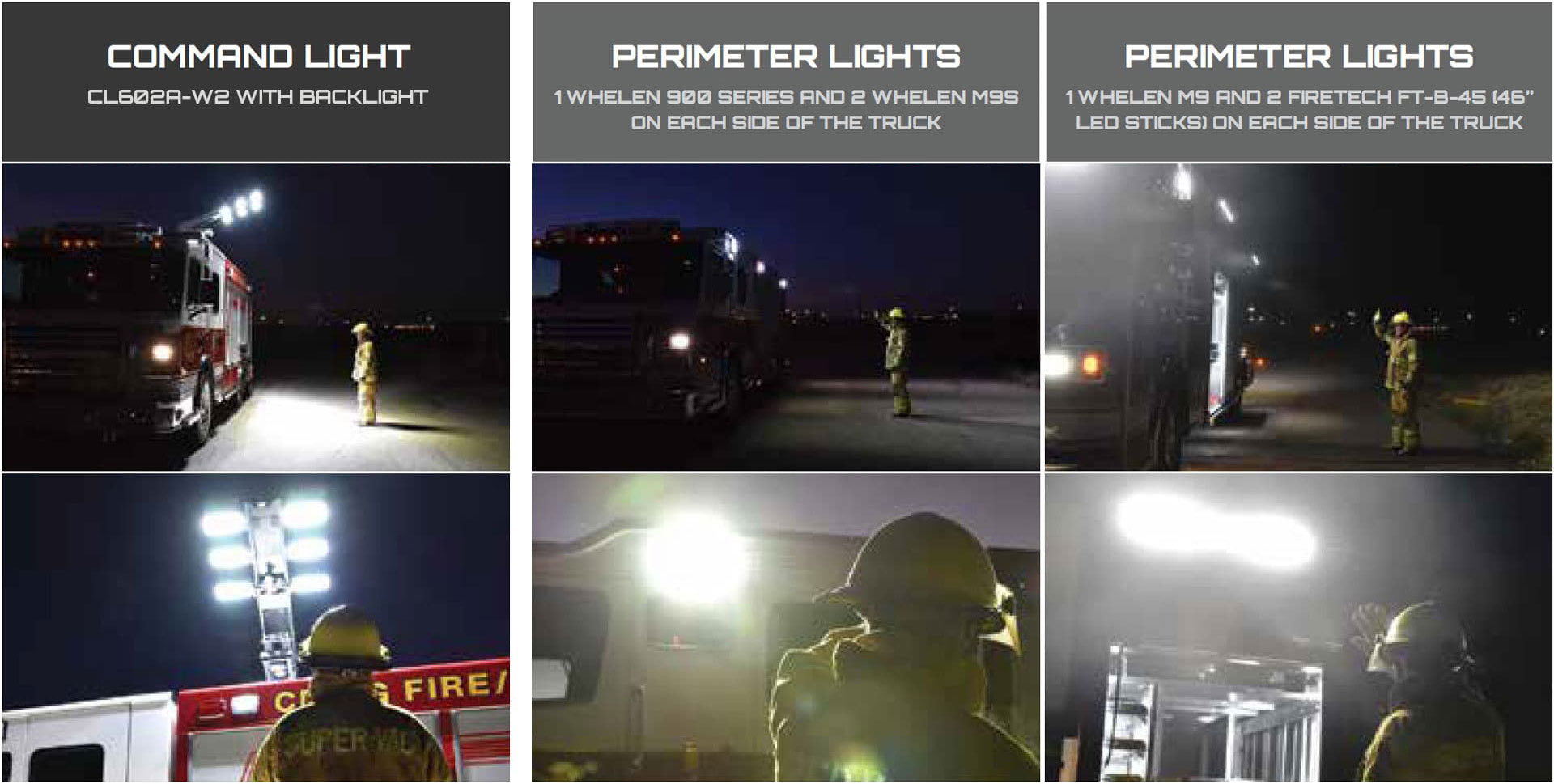

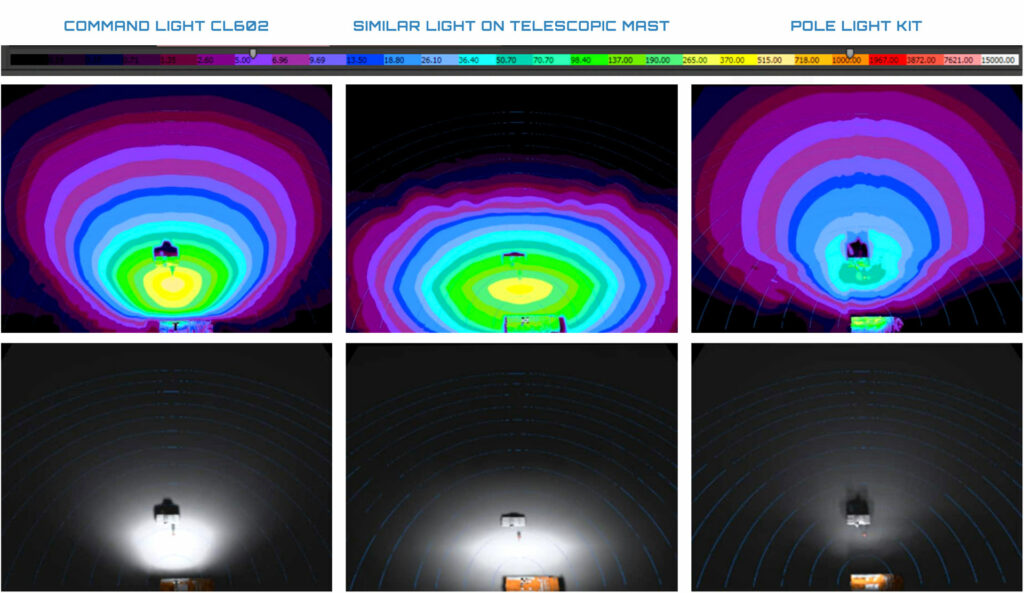

Think of stadium lighting at your favorite sports arena. Much like a fire truck light mast, arena lights are clustered together to gather and direct light to create uniform lighting across the entire arena. The same holds true for the fire truck lighting. These photos compare a six-head tower to two different perimeter light scenarios. In the latter two photos, only half of the truck-mounted lights are directed at the scene, creating unlit areas and sub-par lighting.

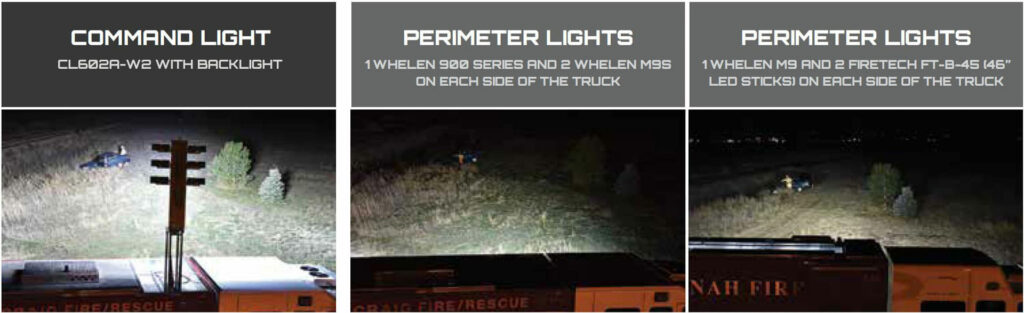

Similarly, this light plot helps visualize the intensity.

“The whole thing about lighting is to make sure it’s usable,” says Roger Weinmeister, President of Command Light, which manufactures light towers for departments around the globe. “The moment you fix lighting to the side of your truck is the moment you lose half the light, which is not a great investment given the expense of LEDs.”

Meanwhile, light towers not only cluster these fixtures, Weinmeister adds, but they can be rotated and angled into endless positions to illuminate ditches, mountain slopes and other terrain. Some towers, like Command Light, offer backlighting capabilities to illuminate dual scenes.

Like the first fundamental, our second lighting principle builds on human anatomy.

“Humans have evolved to work with the sun shining down from overhead,” explains Sam Massa, HiViz President and Chief Technologist for HiViz LED Lighting, a manufacturer of specialty scene lighting. “Here’s the science: Humans have two eyeballs, each recessed into a socket on the frontal bone of the skull. Above that socket, there is a bony structure called the supraorbital ridge over which the eyebrows typically align. When the sun shines down, this bony structure casts a shadow that typically occludes the eye, preventing the sun from shining directly into a person’s eyes as he or she works.”

In short, our bodies (and more specifically our skulls) are built to mitigate this glare. However, at night, if the truck’s lights are fixed directly to the apparatus, all of this goes to the wayside. Massa stresses that it’s important to select lighting options that will place fixtures high overhead to reduce this very glare.

But how high is too high? The intensity of light decreases the farther it is away from an object. Light intensity findings like the one below can help you pinpoint optimal height. In the below light plot, the documented light tower produced 20 meters of usable light by elevating the cluster of lights 9 meters above the truck. Meanwhile, the telescopic mast raised the lights 10 meters high but only produced 15 meters of usable light, while the pole light kit had even less reach because the lights were not clustered together, stressing Fundamental #1.

With light comes shadows, but shadows can often be avoided if a light is properly positioned. Take for instance a stepped pumper body. If a light is mounted above the pumper’s stepped ledge, the light’s optics will hit a portion of the ledge, which in turn will cast a shadow on the work area below. That’s where a light tower light Command Light comes in handy. This tower can be positioned to overhang the side of the apparatus in a “streetlight” position.

But the work area extends beyond the truck. Vehicles, property and even terrain, like ditches or ravines, are all work areas that have shadowed obstacles. But when light is elevated, rotated and angled, these shadows can be managed, and there’s no better way to control the placement of light than with a mast.

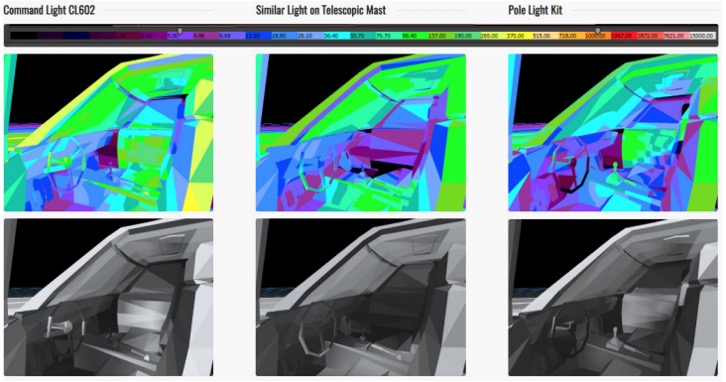

In this third light intensity plot, a vehicle was placed roughly 10 meters from the apparatus light source. Here, both height and light angle impacted the amount of usable light inside the vehicle.

This is a good point to talk about the difference between lux and lumens. Lumens is the total amount of light a fixture produces. However, this number does not represent lux — the amount of light that reaches the scene, or in this case inside the vehicle. As we’ve already addressed, a lot can factor in how many lumens make it to the fireground.

“Every scene is different, so it’s important lighting be versatile,” Weinmeister concludes. “And when you have the ability to control light and how it’s grouped, placed and elevated, your apparatus will become an even more powerful tool.”

And so, with a little urgency, light towers can be more than just an option. They can be a necessity.

“When you’re out at night, saving lives and protecting property, there shouldn’t be a substitute,” Weinmeister says. “And just because it’s not the standard, departments can insist it become one.”

More on LIGHT INTENSITY RESEARCH